The last seven year have seen too little progress on solving the climate change problem, despite some welcome developments. Much more rapid progress is now needed.

It is now seven years since I started this blog – my first post was on 3rd March 2013. It seems a good time to take a look at what has gone well and what has gone badly over that period in efforts to reduce climate change. So here are seven ways in which things have gone badly, and seven ways in which they have gone well.

Things that have gone badly over the last seven years

- Annual CO2 emissions from energy and industry have increased over the last seven years, continuing the long-term trend, when they need to be decreasing rapidly.

Chart 1: Emissions of CO2 from energy and industry (excluding land use)

Source: EDGAR https://edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu/booklet2019/Fossil_CO2andGHG_emissions_of_all_world_countries_booklet_2019report.pdf

- Deforestation has not fallen – if anything it’s increased.

This not only bad for the climate, it’s bad for biodiversity and the wider stability of ecosystems.

Chart 2: Tropical primary forest loss (million hectares)

See: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-48104037

- Over 15% of the remaining carbon budget has been used since 2013, even on the most optimistic view[i].

In 2013 the remaining carbon budget (that is, total cumulative CO2 emissions that remain possible while limiting global mean surface temperature rises to 2 degrees) was around 1900Gt CO2. It is now around 1600Gt CO2.The remainder is getting used up ever more quickly as emissions continue to rise.

- Large amounts of high carbon infrastructure are still being built.

This includes large amounts of new coal-fuelled power generation. This risks lock-in of emissions for decades.

- There is a lack of progress with developing and implementing low carbon technologies in many sectors

Most emissions intensive industries, notably steel, have made little progress in changing their processes to reduce emissions. One of the main technologies likely to be needed for decarbonising industrial emissions, CCS, has seen very little deployment, with only about an additional 10 mtpa[ii] stored from projects coming on line since 2013. The largest contributor to the increase has been the Gorgan project, which is natural gas production, so not likely to be part of a net zero emissions world. 10 mtpa is only about 0.02% of global emissions. CCS is also likely to be essential for achieving negative emissions from Bioenergy with CCS (BECCS), among other things. There has also been only very limited progress to date on deploying low carbon hydrogen.

- China appears to be making emissions reduction less of a priority.

Among other factors, recently slowing economic growth seems to have focussed attention in China towards economic stability and energy security rather than the threats from climate change.

- Most countries have targets that are far too weak

Existing pledges under the Paris Agreement imply a continuing increase in global emissions rather than the rapid decrease that is needed[iii].

This is a daunting list of problems. However, there is also some good news, although in all cases it would be even better if positive trends were happening faster.

Good news from the last seven years

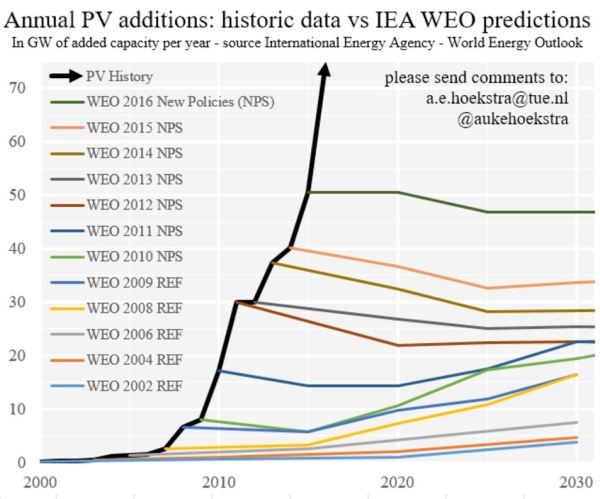

- Costs of low carbon technologies have fallen rapidly, and continue to fall.

Wind and solar electricity are in many cases now competitive with, and often cheaper than, electricity from new fossil fuel generation. Falling battery costs will enable to the electrification of surface transport and help balance the grid.

This seems to me to be by far the greatest cause for optimism. Low carbon options will simply become the default choice for new investment in many cases, and policies to reduce emissions will increasingly be working to support a trend that is driven by economic as well as environment imperatives.

- Some countries have put binding targets in place for net zero emissions.

The UK already has such a target for 2050, seeking to end the UK’s contribution to climate change. The EU seems likely to formalise a similar target very soon.

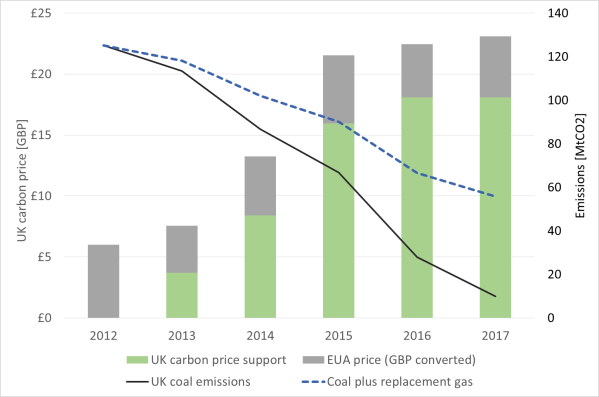

- Some countries have cut emissions significantly, showing what can be done.

The UK has cut its annual emissions by nearly 20% since 2013[iv], with the largest component of this being a reduction in coal use in the power sector, a change readily replicable elsewhere.

- Public concern about climate change has risen while scepticism about the science has largely disappeared, at least outside the USA and a few other countries.

85% of UK voters are now concerned about climate change[v] with over a quarter ranking it among their top three issues[vi]. This was reflected during the recent general election campaign[vii] in all parties offering policies to reduce emissions to net zero . Over time this should create the political space for some of the more challenging policies that will be needed to reduce emissions to close to zero.

- Additional policies are being put in place, and carbon pricing is increasingly widespread.

For example, almost all major economies now have renewables targets, and there are over 50 carbon pricing systems in place around the world.

- Governments increasingly see economic opportunities in decarbonisation rather than costs.

The opportunities created by new industries are increasingly recognised as part of wider industrial policy.

- The Paris Agreement has been signed.

Almost all countries have now committed to limit temperature rises to below 2 degrees and to make a contribution to reaching that target, recognising different national circumstances. Some may consider this is the main piece of good news over the past seven years. However its effectiveness remains to be proven, and its success looks likely to depend on some of the other trends I’ve highlighted, notably falling costs for low carbon technologies.

Looking at these trends together, I am both less optimistic and more optimistic than I was in 2013. I am less optimistic because seven years of rising emissions and continuing investment in high carbon infrastructure have made the challenge of limiting climate change even greater than it was. But I am more optimistic because there is greater recognition and acceptance of the problem, more is now being done (though still nowhere near enough) and, above all, because low carbon energy is rapidly becoming cheaper than high carbon energy. As a result it looks likely that emissions from the energy sector will eventually be greatly reduced and even halted entirely. This may make it easier to focus on reducing other emissions as well, especially those from deforestation.

But eventually will be too late. Much damage is already being done to our world. More will inevitably follow. This will include the loss of irreplaceable parts of the natural world. Given rising emissions, and how much of the carbon budget has been used up, it now looks practically impossible to keep temperature rises to 1.5 degrees, and difficult, though still possible, even to limit them to 2 degrees.

However it could still get much worse. The task now is to avoid the worst of the risks by keeping emissions and accompanying temperature rises as low as possible, including keeping global temperature rises to below 2 degrees. With a lot of effort and a little luck there is still time (just) to achieve this. But the task has never been greater or more urgent.

Adam Whitmore – 9th March 2020

[i] For a 50% chance of remaining below 2 degrees, based on cumulative CO2 emissions. See https://onclimatechangepolicydotorg.wordpress.com/2018/10/

[ii] https://www.globalccsinstitute.com/resources/global-status-report/

[iii] https://climateactiontracker.org/global/cat-emissions-gaps/

[iv] https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/reducing-uk-emissions-2019-progress-report-to-parliament/

[v] https://www.ipsos.com/ipsos-mori/en-uk/concern-about-climate-change-reaches-record-levels-half-now-very-concerned

[vi] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-50307304

[vii] https://onclimatechangepolicydotorg.wordpress.com/2019/11/25/the-uks-political-consensus-on-climate-change/