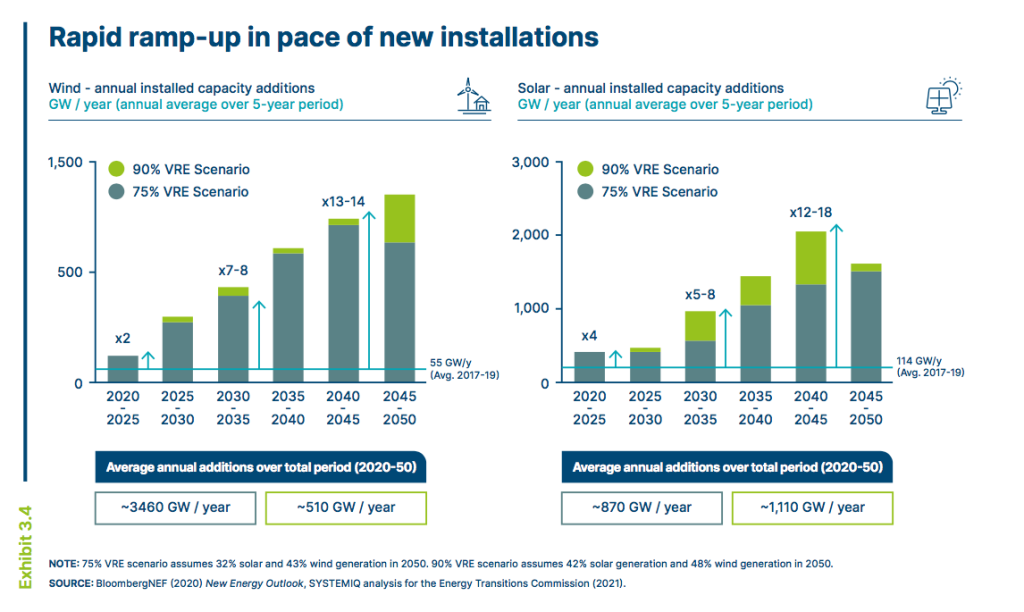

Solar and wind will together need to provide well over half of energy in a decarbonised system. Based on present trends they seem likely to be able to do so, although there will inevitably be challenges.

There are only a few types of energy source which can plausibly make a substantial contribution to a near zero carbon energy system. There are renewables, mainly hydro, wind, solar and bioenergy. Other renewables, including geothermal, tidal and wave energy are likely to continue to be relatively small globally. There is also nuclear, and fossil fuels with CCS.

Currently, these low carbon sources in total account for only around 15% of final energy consumption globally, excluding traditional biomass. This needs to grow to close to 100% over the next few decades.

The predominant role of solar and wind

So, which of the potential sources will provide the bulk of the energy? Here, I assessed plausible maximum contributions over the next few decades are assessed for each energy source, other than solar and wind. The assessment takes account of the following for each energy source.

- Current scale and past growth

- Physical resource constraints, for example for hydro.

- Project development supply chain lead times, for example storage development for CCS

- Scalability

- Costs

With each of the other technologies at their plausible maximum, solar and wind are assumed to fill the remaining gap in energy supply.

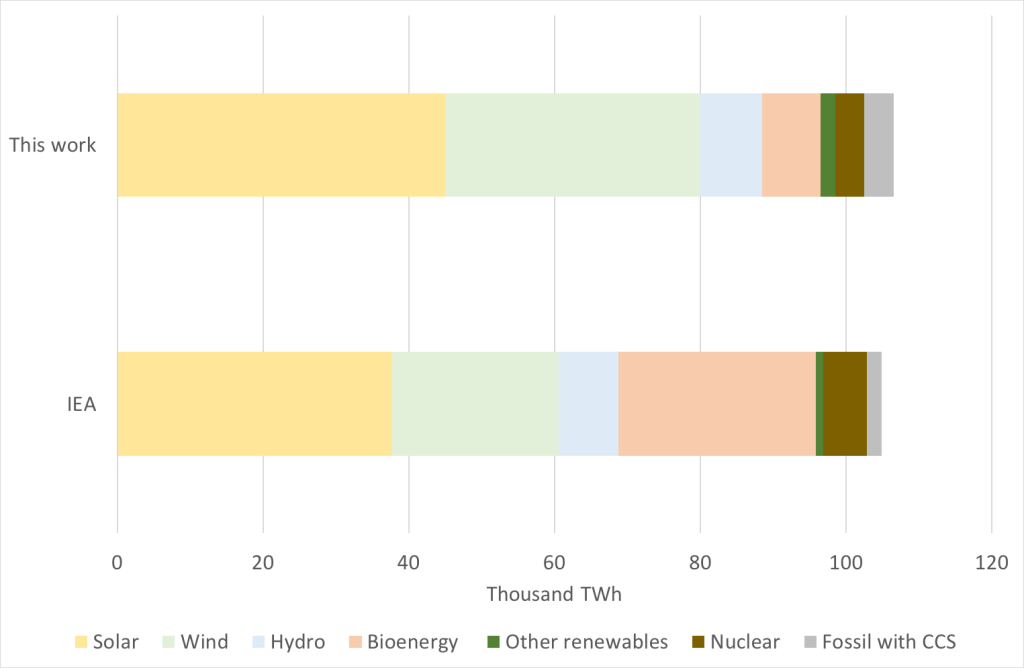

The results of this analysis are shown in Chart 1[i] (see below for brief notes on each energy source). Also shown is recent analysis by the IEA[ii] of potential energy mixes. Although the IEA does not explicitly address the issue of plausible maximums, the estimates are broadly similar in most cases. The exception of bioenergy, where the IEA shows much more than found in the analysis here. Bioenergy will likely be important in some sectors, notably aviation. However the IEA projections seem unlikely on a range of grounds. For example, it is difficult to make bioenergy fully carbon neutral without CCS. In practice demand seems more likely to be met from other sources.

The IEA presents its scenario as being for 2050. However, the 2060s seems a more plausible timescale to reach a near zero carbon system globally, given current circumstances. The estimates in this work are on that basis.

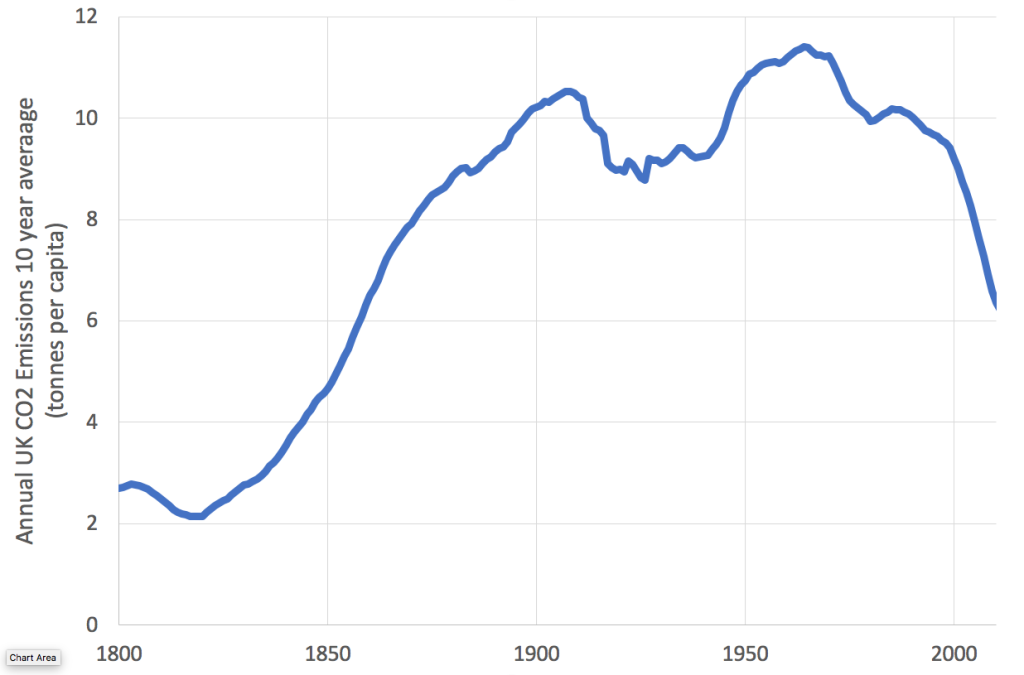

Chart 1: Potential energy mixes for a low carbon system

Notes: Totals here include allowance for losses due to transport, conversion (e.g. to hydrogen) and storage of energy. Solar is mainly PV, but includes a small amount of concentrated solar power. The IEA’s scenario also includes some unabated fossil fuel use which is not included in this chart. Use of heat from nuclear is excluded from this analysis.

The transition to a low carbon system will be helped by increased energy efficiency. Continuing growth of the global population and development of economies will put upwards pressure on energy consumption. However, this is likely to be outweighed by major gains in efficiency from electrification, including use of heat pumps and electric vehicles. Total final energy consumption was around 120,000 TWh in 2022. The IEA projects this will fall to 94,000 TWh for a low carbon system. A slightly greater decrease is included in this work, reflecting the longer time allowed for the transition. Additional energy to meet losses is included in the chart.

Both this work and the IEA scenarios show large amounts of solar and wind[iii]. Indeed, almost any plausible scenario is likely to show solar and wind accounting for over 50% of total energy in a decarbonised system. With more realistic estimates for biomass than assumed by the IEA, solar and wind account for around 75% of energy demand. If, in addition, nuclear or CCS are less successful than assumed, then solar and wind would need to meet close 80% of consumption.

Although solar and wind predominate, other sources will nevertheless be important. The global energy system is vast, so even contributions of a few percent of total consumption are financially large by the standards of most sectors (illustratively, they may be industries each generating revenue of $200-400 billion p.a.).

Is it plausible that solar and wind could generate this much energy by the 2060s or earlier?

Developing such large amounts of solar and wind will be challenging. Fortunately, meeting this challenge is easier because they have a number of characteristics in their favour not matched by any other energy source:

- They are already at scale

- They have demonstrated rapid growth to date, at or near exponential rates

- Costs are already low compared with other forms of energy, and are reducing rapidly

- There is potential for further scalability and standardisation, especially for solar

- The resource base for each is very large and widely dispersed

- Complementary technologies such as batteries and electrolysers to make hydrogen are also growing rapidly and reducing in cost

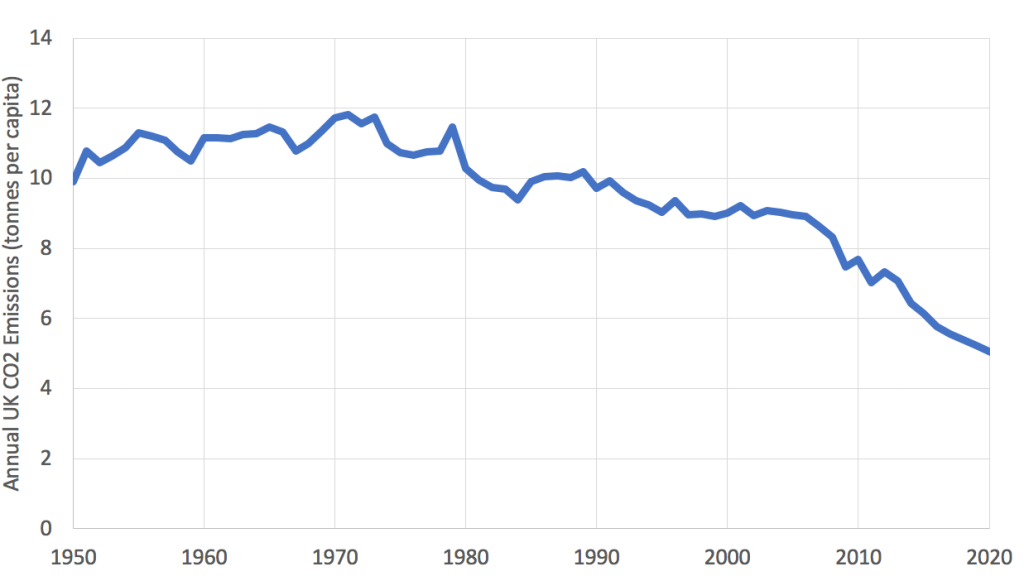

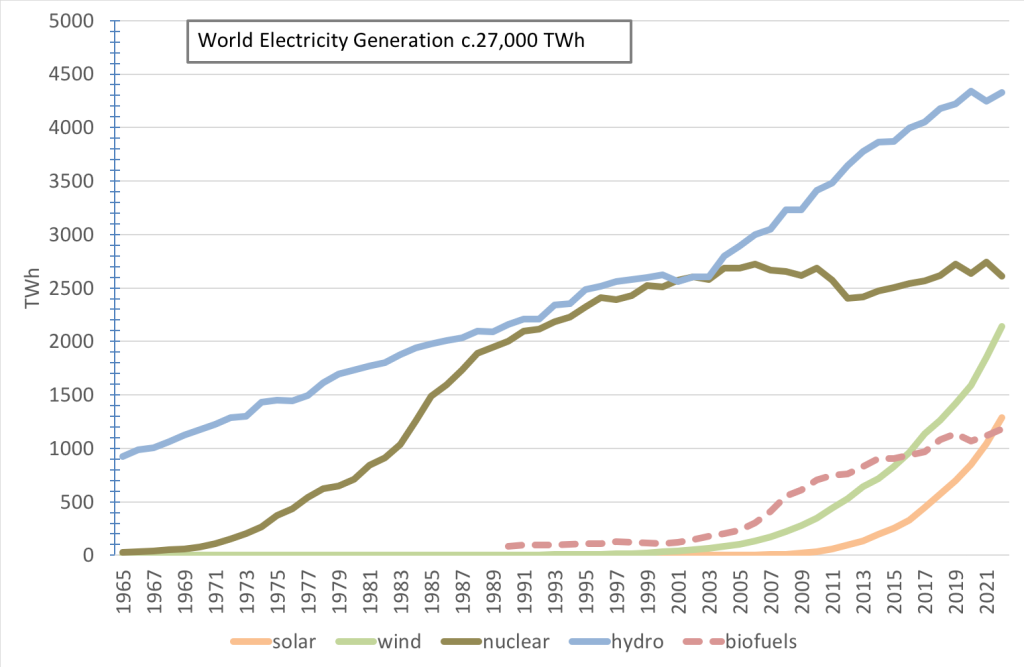

Chart 2 shows the distinctive growth pattern of solar and wind. Nuclear grew rapidly in the 1970s and 1980s but then plateaued. The factors that led to this, notably high costs, do not apply to solar and wind.

Chart 2. Growth of low carbon energy sources to 2022

Source: Our World in Data

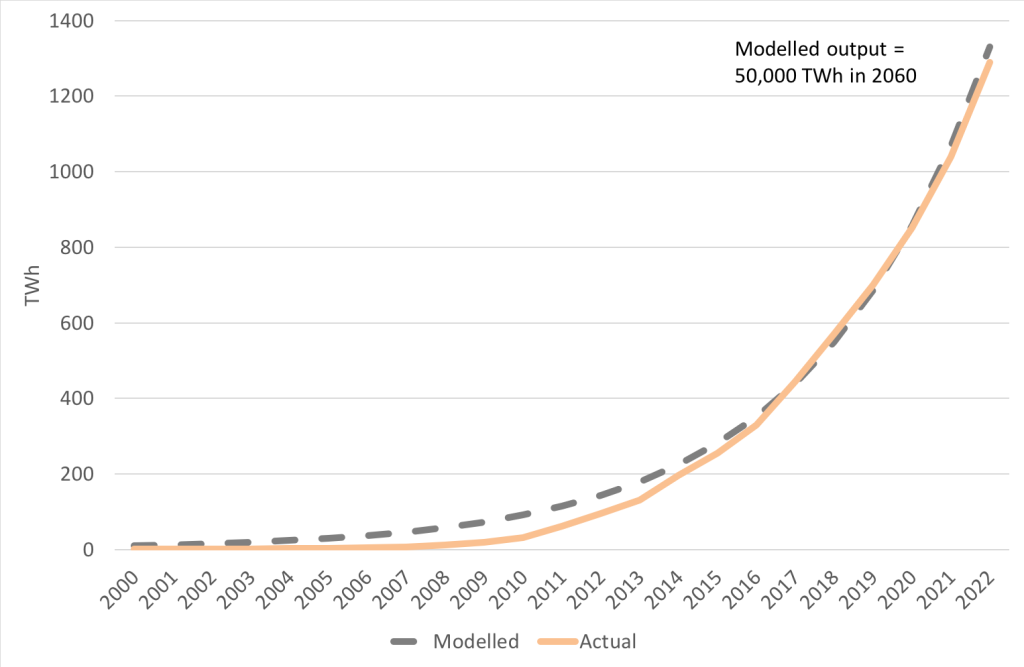

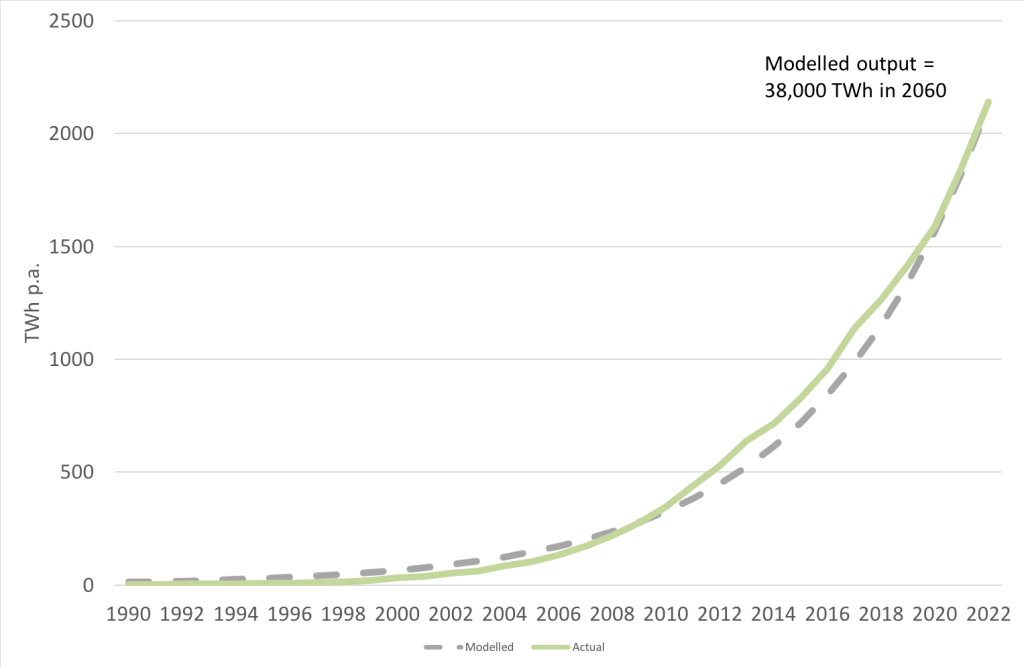

Future deployment of solar and wind are modelled using a standard logistic function (s-curve). The model fits the historic data well, although the fit is not exact and different combinations of parameters give similar results. Growth for both solar and wind are most rapid around 2040, reaching around 2250 TWh p.a. for solar and 1300 TWh p.a. for wind. These rates of installation are around eight and four times 2022 rates respectively.

Chart 3. Modelled and actual generation of solar PV (World)

Chart 4. Modelled and actual generation of wind energy (World)

Generation in 2060 is assumed to increase to up 50,000TWh for solar and 38,000 TWh for wind, more than the approximately 80,000 TWh required to fill the gap in energy supply.

The balance between wind and solar will depend on circumstances and costs. In practice solar seems likely to make a somewhat greater contribution due to rapidly falling costs and continuing scalability. In any case the combined total appears to be comfortably enough to meet demand.

Modelled growt to 2030 is similar to industry protections for both solar and wind. For example, solar industry observers are expecting annual installation rates of 1 TW p.a. by 2030[iv]. Cumulative capacity is around 6 TW by then. This would generate about 9,000TWh p.a. compared with 7,100 TWh p.a. shown here. Wind deployment is expected to be 2000GW, equivalent to around 6200TWh compared with 6,700TWh shown here. Total wind and solar generation is estimated by other observers as 12,000-14,000 TWh in 2030[v], consistent with 13,800TWh shown by this modelling.

The large growth in cumulative capacity should reduce costs. By 2050, solar costs seem likely to fall by a factor of between three and four, and wind costs by a factor of at least two compared with current costs (based on expected deployment and learning rates, and excluding temporary supply chain bottlenecks).

Solar and wind thus look likely to be able to make the required contribution to a near zero carbon energy system. Indeed, there appears to be additional potential for wind and solar if needed. This might be the case if other energy sources produce less than the maximum estimated here, or if demand is higher, for example due to the need for very large amounts of storage for hydrogen, with corresponding conversion losses.

There will of course be huge challenges in meeting such ambitions targets. But they nevertheless appear achievable.

Implications for policy

The central role of solar and wind in a future energy system means that enabling them to continue to scale is crucial. This is greatly helped by falling costs, which increasingly make solar and wind the lowest cost choice for new energy supply. However, there are still areas where growth implies the need for supporting policies.

- Grids. Large scale grid upgrades will be necessary both to transport power over long distances and to balance grids locally. The challenges of grid expansion and upgrades are mainly political rather than technical and economic.

- Storage, especially hydrogen, batteries and heat storage. There is likely to be a complex set of solutions to system balancing, varying with circumstances, including demand management. Markets to help systems balance will have an important role to play in securing innovation and efficient outcomes.

- New technology will continue to play an important role. In particular, more efficient solar cells and floating offshore wind are likely to help meet capacity targets.

- Continued focus on energy efficiency to reduce energy demand, for example insulation of the building stock, will also continue to be required.

The challenge is thus huge. But if the challenge can be met the resulting global energy system will be both better and cheaper than we have now.

Adam Whitmore – 17th April 2024

Notes

Large-scale hydro

Large-scale hydro has grown by about 2000TWh over the last two decades or so, mainly in China, to reach around 4500 TWh. The rate of growth over this period was more than double in absolute turns that in previous decades.

However further growth is limited by the availability of sites. A study showed a theoretical potential of up to 40,000 TWh[vi]. However, another study found exploitable potential of 16,000 TWh[vii]. Even within this total, in practice not all projects will proceed. Extrapolating growth rates from the last two decades to cover the period to the 2060s implies generation of around 8,500 TWh. This is taken this as a likely practical maximum.

Nuclear

Much of nuclear generation comes from aging plant built in the last quarter of the twentieth century. Around 60% of current reactors are over 30 years old[viii], so will come to the end of their lives in the next two decades or so. Growing nuclear generation thus requires that existing capacity is replaced and then that additional capacity is built as well. Current capacity is 395GW, with 64GW under construction[ix].

Lead times for building nuclear plant are long. In the OECD costs are high, as illustrated by the price of over £120/MWh today for Hinkley C in the UK. Indeed nuclear is almost the only technology for which costs have not greatly reduced with deployment – indeed if anything costs have increased (negative learning rates).

Small Modular Reactors may ease cost pressures somewhat but they remain at the development stage and don’t appear to represent fundamentally different technologies.

Based on this it looks like nuclear will face a challenge growing significantly. Examining historic growth rates and likely costs, around 4000 TWh seems the maximum plausible generation by the 2060s, compared with around 2500 TWh today.

Bio energy

Modern bioenergy (i.e. excluding traditional biomass) accounts for around 5.1% of final energy consumption[x].

While there is much uncertainty about future availability, one detailed study has shown that there is little potential for additional use without crossing planetary boundaries[xi]. At the very least there will usually be preferable uses for land, including growing food and landscape restoration.

Bioenergy faces other major challenges.

- It’s expensive, requiring subsides or mandates in most locations

- It is essentially a highly inefficient form of solar energy, and consequently it’s very inefficient in its use of land compared with solar PV, even allowing for losses from conversion of solar electricity to hydrogen when needed.

- It is difficult to make bioenergy fully carbon neutral across the chain without CCS, and then only using fast rotation crops, preferably locally grown.

Furthermore, there is no evidence to date of an ability you scale at the rate that would be required to make a much larger contribution suggested by the IEA. We assume about a maximum of about a third greater than current supply.

Smaller scale renewables

These seem likely to remain relatively small sources of power. These technologies are generally long-standing, but have proved difficult to scale up, due to either technological or commercial barriers. Geothermal energy will be important in Iceland and elsewhere, and seems to have the greatest potential among other renewables. Wave has proved technically challenging as it has been difficult to provide enough robustness against storms while retaining enough flexibility to generate energy. It’s a form of indirect wind energy, and continuing to grow direct wind energy looks more promising. Tidal may have a role to play where tidal ranges are high, but the large amount of civil engineering required usually makes it expensive, and there are often obstacles due to local environmental impacts.

We have assumed they reach 2000TWh, about 20 times greater than today’s levels.

Fossil fuels with CCS

There is clearly no doubt that fossil fuels can provide energy at scale. However, developing CCS has been much slower than many expected. Very little is used for energy, and even if an amount of capture capacity equal to the current global total capture across all applications were devoted to energy from natural gas, it would only provide about 200 TWh. It may manage to scale up, but lead times are long, especially for proving sinks. Costs remain higher than for solar and wind and projects require large amounts of capital.

On balance, it seems unlikely that CCS on energy use it will exceed the energy from nuclear over the next few decades, and the maximum is assumed to equal that for nuclear. CCS may have more of a role to play in decarbonising process emissions.

Nuclear fusion

This is excluded from the analysis. It remains at too early a stage to make a significant contribution over the next 50 years and the free fusion reactor in the sky (the sun) is always likely to be cheaper.

The IEA on solar and wind

The IEA was for many years notorious for forecasting renewables deployment well below outturn. For example, in 2012 they were projecting 23 GW p.a. of solar capacity and 34 GW p.a wind being added in 2023. The actual preliminary figures were around 115 GW for wind[xii], more than four times greater than projected, and 440 GW for solar[xiii], nearly 20 times greater than projected.

[i] The analysis focusses on final energy consumption, with an additional allowance for losses. This is a more useful indicator than primary energy supply, because it excludes the huge losses from fossil fuel power generation and to a lesser extent oil refining. These will not be significant in a low carbon energy system.

[ii] https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-roadmap-a-global-pathway-to-keep-the-15-0c-goal-in-reach

[iii] The two estimates differ by around 30%, which is small compared with the magnitude of the change from current levels.

[iv] https://pv-magazine-usa.com/2022/05/16/a-fate-realized-1-tw-of-solar-to-be-deployed-annually-by-2030/

[v] https://rmi.org/press-release/renewable-energy-deployment-puts-global-power-system-on-track-for-ambitious-net-zero-pathway/

[vi] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2212428422000068

[vii] https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2015/ee/c5ee00888c

[viii] https://www.statista.com/statistics/517060/average-age-of-nuclear-reactors-worldwide/

[ix] https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/current-and-future-generation/nuclear-power-in-the-world-today.aspx

[x] https://www.ren21.net/gsr-2021/chapters/chapter_03/chapter_03/

[xi] https://www.negemproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/D-3.2-Global-NETP-biogeochemical-potential.pdf

[xii] https://gwec.net/globalwindreport2023/

[xiii] https://www.pv-magazine.com/2024/02/20/bloombergnef-says-global-pv-installations-could-hit-574-gw-this-year/#:~:text=It%20said%20that%20new%20solar,and%20722%20GW%20in%202028.