It is often claimed that additional actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in sectors covered by the EUETS are ineffective because total emissions are set by the level of the cap. However this claim is not valid in the current circumstances of the EUETS, and is unlikely to be so even in future. Additional emissions reduction measures in covered sectors can be effective in further permanently reducing emissions.

This post is longer than usual as it deals with a very important but relatively technical policy issue.

The argument about the effectiveness of additional actions to reduce emissions …

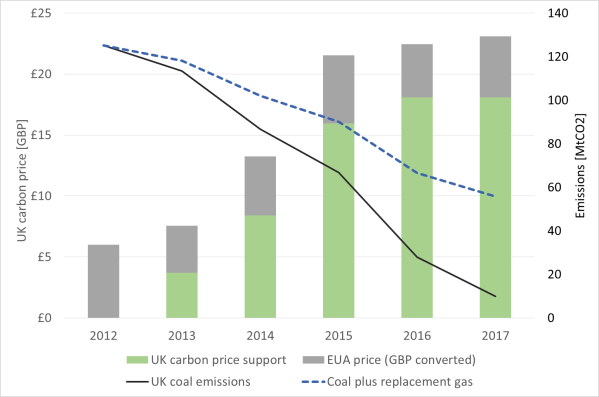

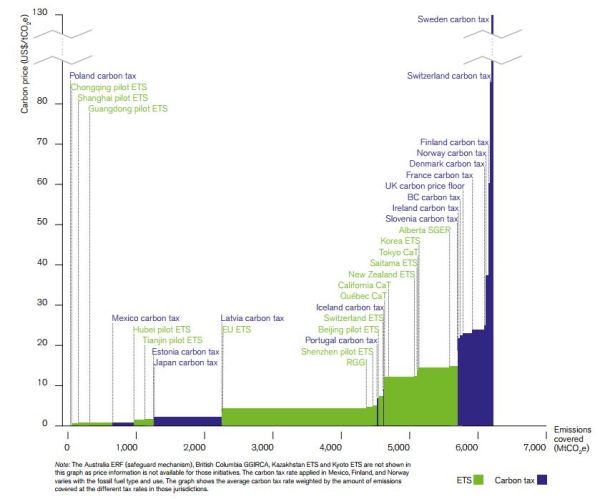

Many additional actions are being taken to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in sectors covered by the EUETS. These include energy efficiency programmes, deployment of renewables, replacing coal plants with less carbon intensive generation, and national carbon pricing.

It is often argued that such additional actions do not reduce total emissions because the maximum quantity of emissions is set by the EUETS cap, so emissions may remain at the fixed level of the cap, irrespective of what other action is taken (see the end of this post for instances of this argument being used publicly).

However, this argument does not stand up to examination.

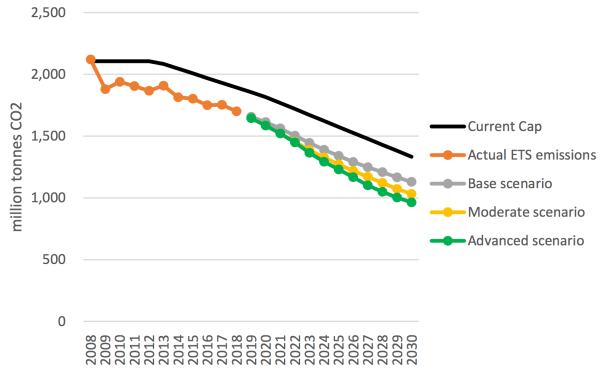

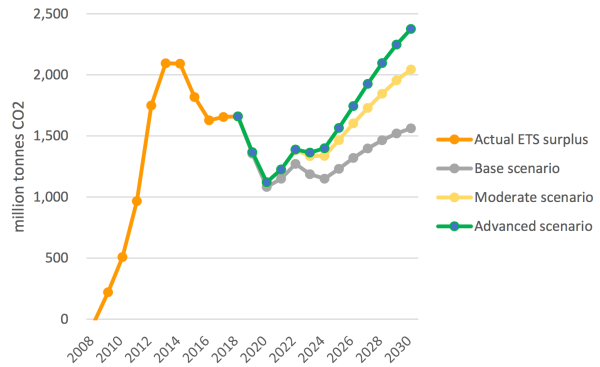

Assessment of the argument needs to take account of the current circumstances of the EUETS. Emissions covered by the EUETS were some 200 million tonnes (about 10%) below the cap in 2015. This year emissions are likely to be 13% below the cap. The EUETS currently has a cumulative surplus of almost three billion allowances, including backloaded allowances currently destined for the Market Stability Reserve (MSR), and the surplus is set to grow as emissions continue to be less than the cap.

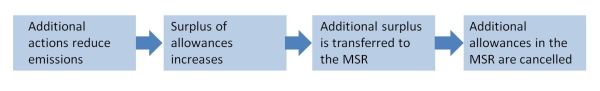

In these circumstances emissions reductions from additional actions will mainly increase the surplus of allowances, with almost all of these allowances ending up in the (MSR). These allowances will stay there for decades under current rules, and so not be available to enable emissions during this time.

Indeed, in practice these allowances are unlikely ever to enable additional emissions. The argument that they will assumes that the supply of allowances is fixed into the long term. In practice this is not the case. Long term supply of allowances is determined by policy, which can and does respond to circumstances. Additional surpluses and lower prices are likely to lead to tighter caps than would otherwise be the case, or cancellation of allowances from the MSR or elsewhere.

The remainder of this post looks at these issues in more detail, including why the erroneous view that additional actions don’t reduce cumulative emissions has arisen.

Why current circumstances make such a difference

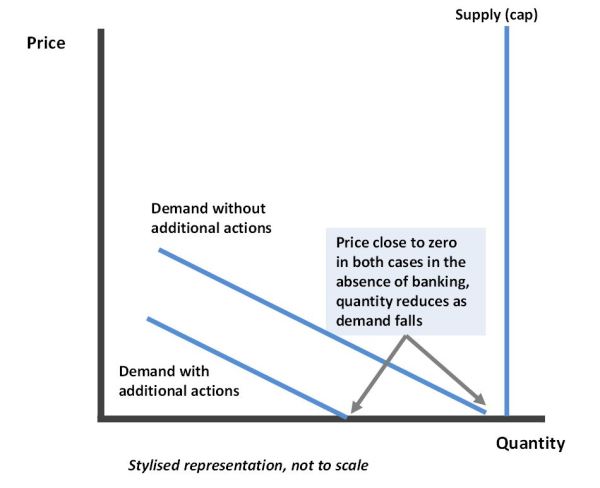

The argument that additional actions to reduce emissions will be ineffective reflects how the EUETS was expected to operate when it was introduced. It was assumed that demand for allowances would adjust so that the quantity of allowances used would always equal to the cap, which was assumed to be fixed.

This is illustrated in stylised form in the diagram below. The supply curve is vertical – perfectly inelastic supply. Demand for allowances without additional actions leads to prices at an initial level. Additional actions reduce demand for allowances at any given price, effectively shifting the demand curve to the left by the amount by which additional actions reduce emissions. This leads price to fall until the lower price creates sufficient additional demand for allowances, so that total demand for allowances is again equal to the supply set by the cap. Because the supply curve is fixed (vertical) the equilibrium quantity of emissions is unchanged, remaining equal to the cap[1].

Chart 1: A price response to the change in demand for allowances can lead to emissions re-equilibrating at the cap when allowances are scarce …

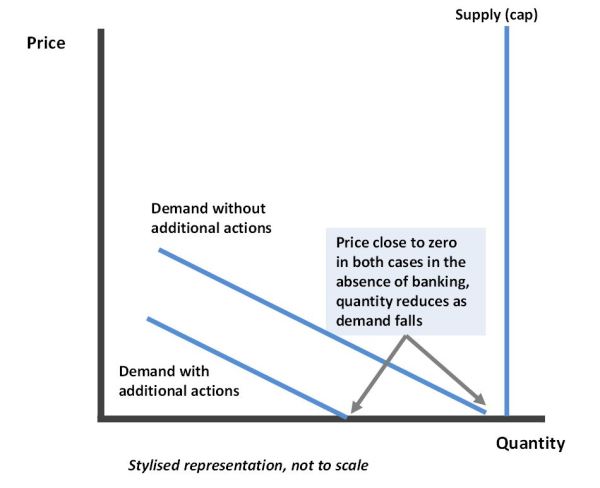

However, at present, large increases in emissions (such that emissions rise to the cap) due to falling prices are clearly not occurring, and they seem unlikely to do so over the next few years. As noted above, the market remains in surplus both cumulatively and on an annual basis. The price would be close to zero in the absence of banking of allowances into subsequent phases, because there would be a cumulative surplus over Phase 3 of the EUETS, and so no scarcity[2].

If demand were further reduced in the absence of banking there would be no price fall, because prices would already be already close to zero. Correspondingly, there would be no increase in demand for allowances to offset the reduced emissions from additional actions. The emissions reductions from additional actions would be retained in full. This is again illustrated in stylised form in the diagram below.

Chart 2: With a surplus of allowances and price close to zero (assuming no banking) any reduction in demand for allowances will be retained in full …

In practice the potential to bank allowances and the future operation of the MSR supports the present price. It is expected that in future as the cap continues to fall allowances will become scarce. There is thus a value to allowances set by the cost of future abatement.

Additional actions now to reduce emissions increase the surplus, and so postpone the expected date at which the market returns to balance. This reduces current prices. This will in turn lead to some increase in emissions. However, this increase will be small – much smaller than if the market were short of allowances now.

Quantifying this effect

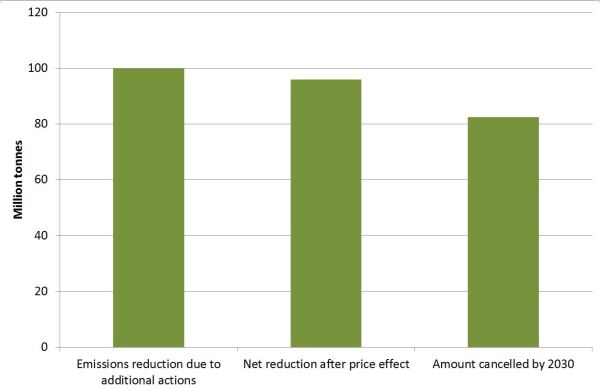

Modelling indicates that if additional actions are taken over the next 10-15 years, then the increase in demand for allowances due to falling price will be less than 10% of the size of the reduction in emissions[3]. Correspondingly more than 90% of the emissions reductions due to additional actions are retained, adding to the surplus of allowances which, which end up in the MSR. Modelling parameters would need to be in error by about an order of magnitude to substantially affect this conclusion.

This effect arises in part because of the low level of prices at present. This means that even a large percentage change in price leads to a small absolute change, and thus a small effect on demand for allowances. Even a 50% price fall would be less than €3/t at current price levels. It also reflects that the shape of the Marginal Abatement Cost curve, with price falls only increasing abatement by a small amount. This means that even if prices are higher than current levels the effect of price falls on demand for allowances is still relatively small.

The relatively small response to price changes is consistent with the current market, where there is a lack of sufficient increase in demand to absorb the current yearly surplus (or even to come close to doing so).

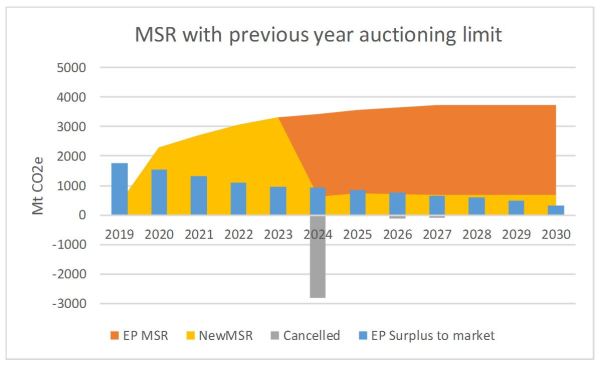

The 90%-plus of the allowances freed up by additional actions are added to the surplus end up over time in the MSR. They then stay there for several decades. This is because even without additional actions, and even with some reform of the current proposals for Phase 4 (which covers 2021 to 2030), the MSR is likely contain at least three billion allowances by 2030, and perhaps as much as five billion. This will take until 2060 to return to the market, and perhaps until the 2080s, at the maximum rate written into the legislation of 100 million per annum.

Any additional surplus will only return after this. Even if the return rate of the MSR were doubled the return time for additional surplus would still be reckoned in decades from now.

This will be even more the case if proposals for the EUETS Phase 4 are not reformed, and the surplus of allowances being generated anyway is correspondingly greater.

The implications of the very long delay in the return of allowances

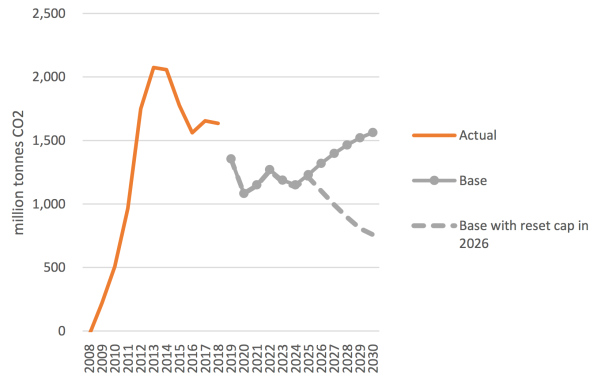

It seems unlikely that allowances kept out of the market for so long would ever lead to additional emissions. It would require policy makers to allow the allowances to return and enable additional emissions. This would be at a time when emission limits would be much tighter than they are now, and indeed with a commitment under the Paris Agreement to work towards net zero emissions in the second half of this century.

There are several policy mechanisms that could prevent the additional surplus allowances enabling emissions. Subsequent caps tighter as unused allowances reduce the perceived risk of tighter caps, and additional actions now set the economy on a lower carbon pathway. Furthermore, with a very large number of allowances in the MSR over several phases of the scheme, allowances may well be cancelled. Indeed, over such long periods the ETS itself may even be abolished or fundamentally reformed, with allowances not carried over in full. Or a surplus under the EUETS may persist indefinitely as additional actions succeed in reducing emissions.

As the market tightens towards 2030 it is likely that a higher proportion of any additional emissions reductions will be absorbed by the market via a price effect, but it still seems unlikely to be as much as 100% given the long term trend to lower emissions and the lack of additional sources of demand, especially in the event of large scale additional actions[4]. Some of the policy responses described would still be expected to reduce the supply of allowances.

Conclusions

The argument that emissions will always rise to the level of the cap manifestly does not hold at present, when emissions are well below the cap. and there is a huge cumulative surplus of allowances.

In future, it seems likely that more than 90% of reductions in emissions from additional actions will simply add to the surplus, and eventually end up in the MSR. They at least stay there for several decades, because of the very large volume that will anyway be in the MSR.

While there is in principle a possibility that they will eventually return to the market and allow additional emissions this appears most unlikely in practice. Policy decisions will be affected by circumstances and this can readily prevent additional emissions, through some combination of tightening of the cap and cancellation of allowances.

Even when the market returns to scarcity these policy responses are likely to hold to a large extent, for example with lower prices enabling more stringent caps. The hypothesis of no net reductions in emissions from additional actions thus seems unlikely ever to hold true.

Spurious arguments about a lack of net emissions reductions should not be used as a pretext for failing to take additional actions to reduce emissions now.

Adam Whitmore – 21st October 2016

Note: A more detailed review of the issues raised in this post, and the accompanying modelling can be found in this report.

Examples of statements invoking the idea of fixed total emissions

For example, in 2015 RWE used such arguments in objecting to the closure of coal plant:

“The proposals [to reduce lignite generation] would not lead to a CO2 reduction in absolute terms. [The number of] certificates in the ETS would remain unchanged and as a result emissions would simply be shifted abroad.” [5]

Similarly, in 2012 the then Chairman of the UK’s Parliament’s Energy and Climate Change Select Committee, opposed the UK’s carbon price support mechanism for the power sector arguing that:

“Unless the price of carbon is increased at an EU-wide level, taking action on our own will have no overall effect on emissions”[6]

Neutral, well-informed observers of energy markets have also made this case. For example, Professor Steven Sorrel of Sussex University recently argued that:

“Any additional abatement in the UK simply ‘frees up’ EU allowances that can be either sold or banked, and hence used for compliance elsewhere within the EU ETS”[7]

[1] This is analogous to the well-established rebound effect for energy efficiency measures. Improved domestic insulation lowers the effective price of energy, so consumers take some of the benefits as increased warmth, and some as reduced consumption. The argument here is that in effect there is a 100% rebound effect for emissions reductions under the EUETS.

[2] Such a situation occurred towards the end of Phase 1 of the EUETS (2005-7), which did not allow banking into Phase 2. Towards the end of the Phase there was a surplus of allowances and the price fell to close to zero.

[3] The price change is modelled by assuming the price is set by discounting future abatement costs, with a later date for the market returning to balance leading to greater discounting and so a lower price. The increase in demand for allowances is modelled based on a marginal abatement cost curve and consideration of sources of additional demand. See report referenced at the end of this post for further details of the modelling.

[4] There are likely to be path dependency and hysteresis effects in the market which prevent a full rebound.

[5] See RWE statement, “Proposals of Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy endanger the future survival of lignite”, 20 March 2015. http://www.rwe.com/web/cms/en/113648/rwe/press-news/press-release/?pmid=4012793

[6] http://www.parliament.uk/briefing-papers/sn05927.pdf

[7] http://www.energypost.eu/brexit-opportunity-rethink-uk-carbon-pricing/