Europe is progressing with phasing out hard coal and lignite in power generation, but needs to move further faster, especially in Germany and Poland

Reducing coal use in power generation and replacing it with renewables (and in the short run with natural gas) remains one of the best ways of reducing emissions simply, cheaply and quickly at large scale. Indeed, it is essential to meet the targets of the Paris Agreement that the world’s limited remaining cumulative emissions budget is not squandered on burning coal and lignite in power generation.

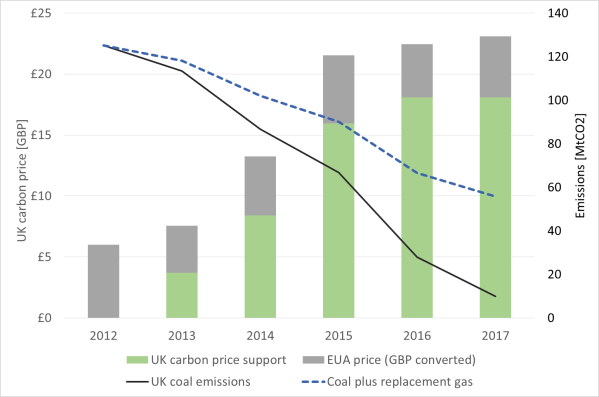

Europe is now making progress in phasing out coal. The UK experience has already illustrated what can be done with incentives from carbon pricing to reduce coal generation. Emissions from coal have reduced by more than 80% in the last few years, even though coal plant remains on the system[i]. However, many countries, including the UK, are now going further and committing to end coal use in power generation completely in the next few years. The map below shows these commitments as they now stand. Most countries in western Europe now have commitments in place. (Spain is an exception. The government is expecting coal plant to be phased out by 2030, but currently does not mandate this.)

Map: Current coal phase-out commitments in Europe[ii]

Source: Adapted from material by Sandbag (see endnotes).

In some countries there is little or no coal generation anyway. In other countries plants are old and coming to the end of their life on commercial grounds, or are unable to comply with limits on other pollutants. In each case phase-out is expected to go smoothly.

However, the largest emitters are mainly in Germany and Poland and here progress is more limited. Germany has now committed to coal phase-out. But full phase-out might be as late as 2038. Taking another 20 years or so to phase out such a major source of emissions is simply too long. And Poland currently looks unlikely to make any commitment to complete phase out.

This means the Europe is still doing less than it could and should be doing to reduce emissions from coal and lignite. As a result, EU emissions are too high, and the EU loses moral authority when urging other nations, especially in Asia and the USA, to reduce their emissions further, including by cutting coal use.

Several things are needed to improve this situation, including the following.

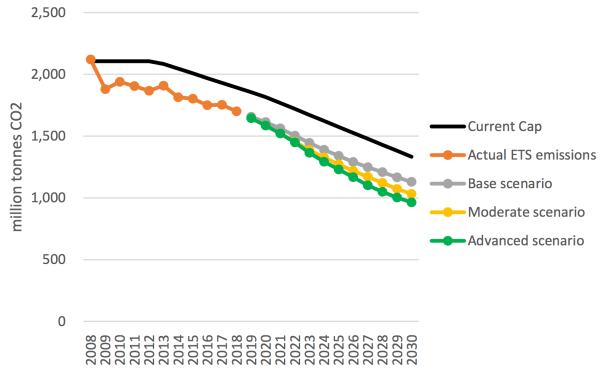

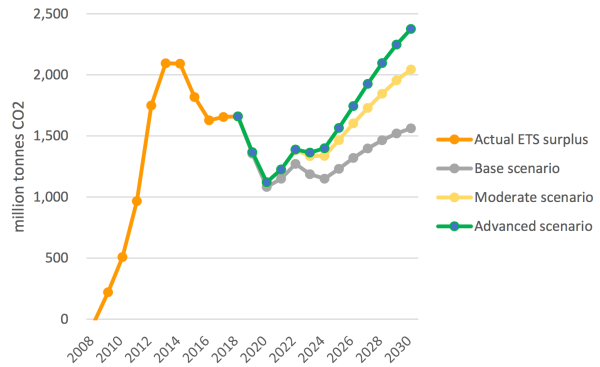

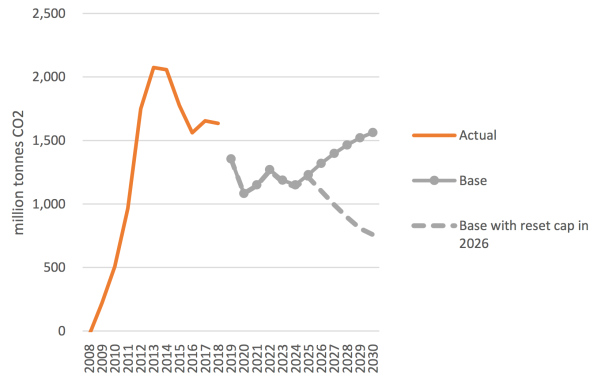

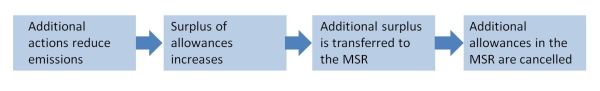

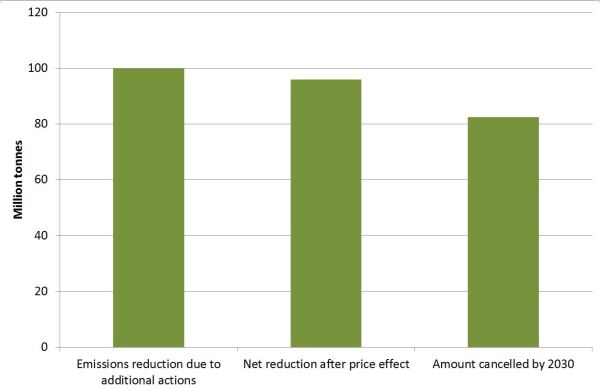

- Further strengthening the carbon price under the EUETS by reducing the cap. I looked at the problem of continuing surpluses of allowances in another recent post, and accelerated coal closure would make the surplus even greater. Although the rise in the EUA price in the last 18 months or so is welcome, further strengthening of the EUETS is necessary to reduce the risk of future price falls, and preferably to keep prices on a rising track so they more effectively signal the need for decarbonisation.

- Continuing tightening of regulations on other pollutants, which can improve public health, while increasing polluters’ costs and therefore adding to commercial pressure to close plant.

- Strengthening existing phase out commitments, including be specifying an earlier completion date in Germany.

- Further enabling renewables, for example by continuing to improve grid integration, so that it is clear that continuing coal generation is unnecessary.

As I noted in my last post, making deep emissions cuts to avoid overshooting the world’s limited remaining carbon budget will require many difficulties to be overcome. There is no excuse for failing to make the relatively cheap and easy reductions now. Reducing hard coal and lignite use in power generation in Europe (and elsewhere) continues to require further attention.

Adam Whitmore – 18th June 2019

[i] See https://onclimatechangepolicydotorg.wordpress.com/2018/01/17/emissions-reductions-due-to-carbon-pricing-can-be-big-quick-and-cheap/

With and updated chart at:

https://onclimatechangepolicydotorg.wordpress.com/carbon-pricing/price-floors-and-ceilings/

[ii] Map adapted from Sandbag:

https://sandbag.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Last-Gasp-2018-slim-version.pdf

and data in: