Low carbon hydrogen and electricity via heat pumps may both play a large role in decarbonising building heating in the UK. Ways forward are needed that maintain optionality around solutions while more is learnt about the right mix.

Decarbonising building heating in the UK poses a range of challenges. First, the required transition is very large scale. There are around 27 million households in the UK, with many more commercial buildings, small and large. This implies around a million or more premises a year on average need to be converted to low carbon heat between now and 2050.

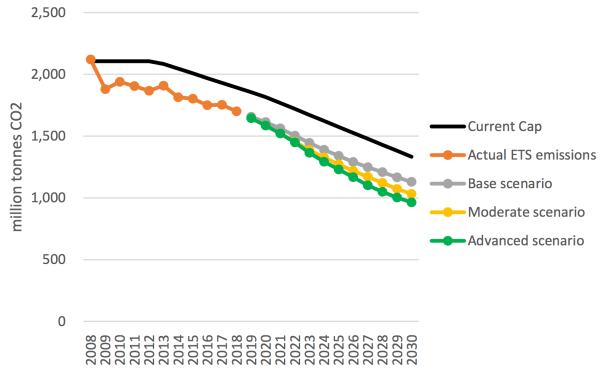

Along with scale, there is cost. Replacing the UK’s heating system is expensive both in total and by household, even if the existing natural gas network can be used for hydrogen. This challenge is made more difficult by the high seasonality of heating demand (Chart 1). Building natural gas supply chains, reformers to produce hydrogen from natural gas, CCS, low carbon electricity and heat pumps all involve major capital investment. Running this for only part of the year – the colder months – increases unit costs substantially. The chart below shows daily gas and electricity demand from non-daily metered (i.e. small) customers. Demand for energy from gas, the major source of building heating at present, is about two or three times electricity demand during winter, and is much more seasonal.

Chart 1: Heating demand is highly seasonal …

Source: BEIS (2018) ‘Clean Growth – Transforming Heating’ https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/766109/decarbonising-heating.pdf

Furthermore, the transition to low carbon heat needs to be made largely with the UK’s existing building stock, which is mainly old and often badly insulated. Improved insulation is a priority in any programme, but there are practical and cost constraints on what can be done with existing buildings. (Buildings also need to be able to cope with the increased prevalence of heat waves as the climate warms, but that is a separate topic.)

Finally, building heating directly affects people’s day to day lives, so consumers’ acceptance is critical. On the whole the present system, based mainly on natural gas boilers, works quite well except for its emissions. Any new system should preferably work as well or better.

The leading candidates for low carbon heating in buildings are electricity, almost certainly using heat pumps to increase efficiency, and low carbon hydrogen. Biomass seems unlikely to be available either at the scale or cost that would be needed for it to be a major contributor to low carbon heating, though it may find a niche. District heating networks require low carbon heat and this must draw on the same ultimate set of sources of heat. Waste heat from nuclear, once discussed as a possibility, no longer seems likely to be either practical or cost effective.

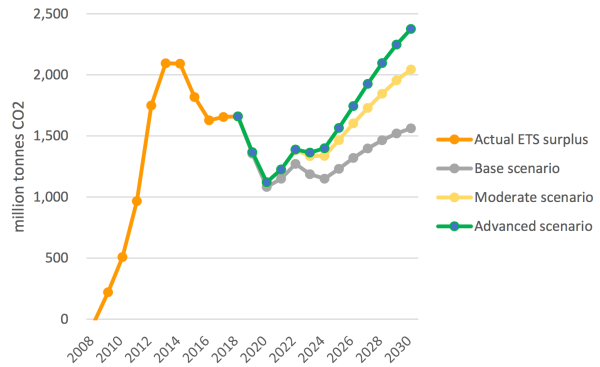

Recently the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) analysed the costs of decarbonising heat in 2050 using different approaches. They looked at electricity, hydrogen, and combinations of the two. The analysis concluded that a 50% increase over current costs was likely (Chart 2). The remarkable thing about the analysis is that this cost was similar for all of the options considered. Any differences were well within the uncertainty of the estimates.

Chart 2: Costs of different modes for decarbonising building heating …

Source: Committee on Climate Change

With no large cost difference leading to one or the other option being preferred there is a need to test each option out to see which works better in practice. Mixed solutions may be appropriate in many cases. For example, hydrogen may be useful in providing top-up heat even if heat pumps are providing the baseload, or may be the only solution for some poorly insulated properties for which heat pumps don’t run at high enough temperatures.

The CCC’s analysis includes expected cost savings. The transition to low carbon heat will clearly be more acceptable if this cost can be reduced further. In particular there seem likely to be both technical advances and large economies of scale in heat pump manufacture and installation, and the costs of low carbon power may fall by more than assumed by the CCC. As the analysis stands, a 50% increase is clearly politically difficult, especially when there do not seem to be advantages for the customer, and potentially some drawbacks. However, this is less than a 2% p.a. compound increase in real terms over a 30 year period, which might be politically feasible if introduced gradually and spread across all consumers.

With such large changes in demand between summer and winter, seasonal storage is a major issue for reasons of both cost and practicality. This is an under-researched area, and needs further work. There are various possibilities – storage of hydrogen itself in salt caverns, storage of hydrogen as ammonia or storage of heat in ground sinks, but each has its problems and the scale involved is very large.

A final uncertainty is the form which hydrogen production will take. At the moment methane in reformers predominates and, with the addition of CCS, may continue to do so. However both the costs of low carbon electricity and of the electrolysis are decreasing rapidly. Over the long term this may become a more significant pathway for hydrogen production.

These uncertainties imply that building heating poses a particularly difficult set of choices for policy. It is not clear what route, or mix of routes, is the right one. The transition needs to be quite rapid relative to the lifetimes and scale of existing infrastructure, and it involves the need for consumer acceptance. There are also potentially strong network and lock in issues.

The best approach is likely to be to develop several types of solution in parallel, maintaining optionality while learning, and being prepared for some approaches to be dead ends. The implications of this include the need for roll out of low carbon heat sources in some districts now to get an idea of how they will work at scale.

Some of this is happening, much more is needed.

Adam Whitmore -29th October 2019.

Comparison of cost estimates with previous analysis by this blog.

Around four and a half years ago I looked at the costs of decarbonising domestic heating in the UK in winter using low carbon electricity. I concluded that switching to low carbon heat would add 75% or more to domestic heating bills, with some drawbacks for consumers (I also looked at higher cost case, but this case no longer seems likely due to the fall in the costs of low carbon electricity, especially offshore wind, since the analysis was done.) I suggested that this meant that the transition would be difficult and that reductions in capital costs were necessary.

This analysis is broadly consistent with the CCC analysis quoted here, which suggests a 50% increase on current costs. The estimates are roughly similar given the large uncertainties involved , the inevitable differences is assumptions, and different basis of the estimates. In particular the CCC analysis factors in reductions in costs of low carbon heating likely by 2050, whereas my previous analysis was based on current costs to make the point that cost reductions are necessary, Consequently it would be expected that the CCC analysis would show a smaller cost increase relative to current costs. Also, the CCC’s analysis may exclude some costs – estimates such as these have a tendency to go up when you look at them more closely. Equally it may understate the cost reductions possible over decades.