Some simple indicators based on stylised emissions tracks help show clearly the consequences of different rates of emissions reductions.

A simple relationship allows the overall objectives – limiting temperature rises and reducing emissions – to be linked in a straightforward way[i]. Over relevant ranges and timescales temperature rise varies approximately linearly with cumulative emissions of CO2, after adjusting for the effect of other greenhouse gases. Specifically, for every 3700 GtCO2 emitted (1000GtC) the temperature will rise by about 2.0 degrees[ii] (with estimates in the range 0.8 to 2.5 degrees)[iii]. This is the transient climate response to cumulative emissions (TCRE).

There has been around a 1.0 degree rise in temperatures to date[iv]. This means the remaining total of cumulative emissions (“carbon budget”) needs to be small enough to keep further temperature rises to around 0.5 to 1.0 degrees if it is to meet targets of limiting temperature rises to 1.5 to 2.0 degrees.

The remaining carbon budget for meeting a 1.5 degree target (with 50% probability) is around 770 GtCO2. The remaining carbon budget for meeting a 2 degree target (again with 50% probability) is 1690 GtCO2[v]. This is illustrated in Chart 1, which shows temperature rise (median estimates) against additional emissions from 2018.

There are many uncertainties in the estimates of the remaining carbon budget. These include different estimates of the climate sensitivity, variations in warming due non-CO2 pollutants, and the effect of additional earth system feedbacks, including melting of permafrost. These can each change the remaining carbon budget by around 200GtCO2 or more.

Chart 1: Temperature rise from additional emissions

Source: adapted from Table 2.2 in http://report.ipcc.ch/sr15/pdf/sr15_chapter2.pdf

To look at the implications of this simple relationship we can make the following assumptions about future levels of emissions. These are simplistic, but like all useful simplifications, allow the essence of the issue to be seen more clearly.

- Net emissions continue approximately flat at present levels (of around 42 GtCO2a.[vi]) until they start to decrease.

- Once net emissions start decreasing they continue decreasing linearly to reach zero – when any continuing emissions are balanced by removals of CO2 from the atmosphere. They then continue at zero. There are of course many other emissions tracks leading to the same cumulative emissions. For example, many scenarios include negative total emissions, that is net removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, in the second half of the century.

- Relatively short-lived climate forcings, such as methane, are also greatly reduced, so that they eventually add about 0.15 degrees to warming[vii].

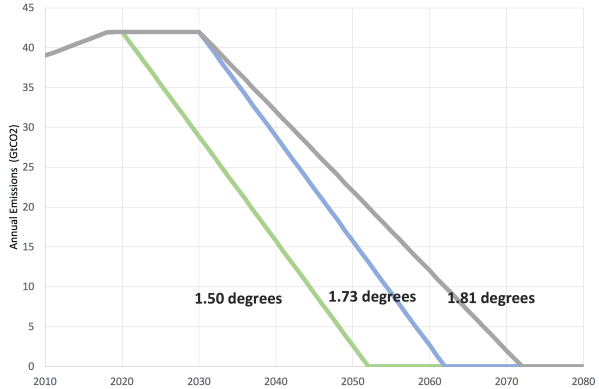

Chart 2 shows various temperature outcomes matched to stylised emissions tracks. Cumulative emissions are the areas under the curves. To limit temperatures rises to 1.5 degrees, emissions need to fall to zero by around 2050 starting in 2020, consistent with the estimates in the recent IPCC report[viii].

For limiting temperature rises to 2 degrees with 50% probability, zero emissions must be reached around 2095. To reach the 2 degree target with 66% probability emissions need to be reduced to net zero about 20 years earlier – by around 2075 from a 2020 start. |To reach a target of “well below” 2 degrees is specified in the Paris Agreement emissions must be reduced to zero sooner.

Chart 2: Stylised emissions reduction pathways for defined temperature outcomes (temperatures with 50% and 75% probability)

This simplified approach yields some useful rules of thumb.

Each decade the starting point for emissions reductions is delayed (for example from 2020 to 2030) adds 0.23 degrees to the temperature rise if the subsequent time taken to reach zero emissions is the same (same rate of decrease – i.e. same slope of the line) – see Chart 3 below. This increase is even greater if emissions increase over the decade of delay. This is a huge effect for a relatively small difference in timing.

Delaying the time taken to get to zero emissions by a decade from the same starting date (for example reaching zero in 2070 instead of 2060) increases eventual warming by 0.11 degrees.

Correspondingly, delaying the start of emissions reductions increases the required rate of emissions reduction to meet a given temperature target. For each decade of delay in starting emissions reductions the time available to reduce emissions to zero decreases by two decades. For example, tarting in 2020 gives about 75 years to reduce emissions to zero for a 2 degrees target. Starting in 2030 gives only 55 years to reduce emissions from current levels to zero once reductions have begun, a much harder task.

Chart 3: Effect of delaying emissions reductions (temperatures with 50% probability)

These results are, within the limits of the simplifications I’ve adopted, consistent with other analysis (see notes at the end for further details)[ix].

How realistic are these goals? Energy infrastructure often has a lifetime of decades, so the system is slow to change. Consistent with this, among major European economies the best that is being achieved on a sustained basis is emissions reductions of 10-20% per decade. While some emissions reductions may now be easier than they were, for example because the costs of renewables have fallen, deeper emissions cuts are likely to be more challenging. This implies many decades will be required to get down to zero emissions.

All of this emphasises the need to start soon, and keep going. The recent IPCC report emphasised the challenges of meeting a 1.5 degree target. But even the target of keeping temperature rises below 2 degrees remains immensely difficult. There is no time to lose.

Adam Whitmore – 23rd October 2018

Notes

[i] This analysis draws on previous work by Stocker and Allen, which I covered a while back here: https://onclimatechangepolicydotorg.wordpress.com/2013/12/06/early-reductions-in-carbon-dioxide-emissions-remain-imperative/

[ii] This is the figure implied in Table 2.2 in http://report.ipcc.ch/sr15/pdf/sr15_chapter2.pdf. All references to temperature in this post are to global mean surface temperatures (GMST).

[iii] IPCC Fifth Assessment Report, Synthesis Report, Section 2.2.4 for the range. The central value is that which appears to have been used to construct Table 2.2 of http://report.ipcc.ch/sr15/pdf/sr15_chapter2.pdf

[iv] The IPCC quotes 0.9 degrees by 2006-2015, which is consistent with 1.0 degrees now.

[v] Table 2.2 of http://report.ipcc.ch/sr15/pdf/sr15_chapter2.pdf

[vi] http://report.ipcc.ch/sr15/pdf/sr15_spm_final.pdfC1.3

[vii] See IPCC 1.5 degree report Chapter 2 for details.

[viii] http://report.ipcc.ch/sr15/pdf/sr15_spm_final.pdf summary for policy makers, see charts on p.6

[ix] See for example work by Climate Action Tracker https://climateactiontracker.org/global/temperatures/, and and the Stocker and Allan analysis cited as reference (i) above. The recent IPCC report Chapter 2 Section C1, concludes: In model pathways with no or limited overshoot of 1.5°C, global net anthropogenic CO2 emissions decline by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 (40–60% interquartile range), reaching net zero around 2050 (2045–2055 interquartile range). For limiting global warming to below 2°C CO2 emissions are projected to decline by about 20% by 2030 in most pathways (10–30% interquartile range) and reach net zero around 2075 (2065–2080 interquartile range). Non-CO2 emissions in pathways that limit global warming to 1.5°C show deep reductions that are similar to those in pathways limiting warming to 2°C.” References in this paragraph to pathways limiting global warming to 2C are based on a 66% probability of staying below 2C.